How much capital can startups profitably eat?

Welcome to Cautious Optimism, a newsletter on tech, business, and power.

📈 Trending Up: Censorship on social media … breaking the law … DeepSeek bans … US-China tariffs … tech-lash … regional AI dealmaking at OpenAI … agentic ecommerce … Canadian startups …

Coups: The usually sober folks at TechDirt write that “a coup is underway in the United States, and we must stop pretending otherwise.” The argument? “Donald Trump and Elon Musk are systematically seizing control of the federal government’s machinery through plainly illegal means.”

The Verge seems to agree, saying of the Musk-led takeover of government “it seems [its] clear goal here amounts to a coup over the administrative state.”

CO: Does Trump know what Musk is doing? His comments yesterday that Musk can only fire people with permission doesn’t mesh at all with what the businessman is actually up to. Much hay was made over Biden’s age, and the chance that he was being managed from behind by shadowy figures. In this case, an aged president is being managed from the front by the most visible person of all time. (CO is not alone in its vibe of who currently holds power in Washington, and who does not.)

📉 Trending Down: Competent mangement … tariffs on China, Mexico, after some phone calls … AI hallucinations … forcing ourselves to move … getting work done …

Is there an upper limit to venture investment?

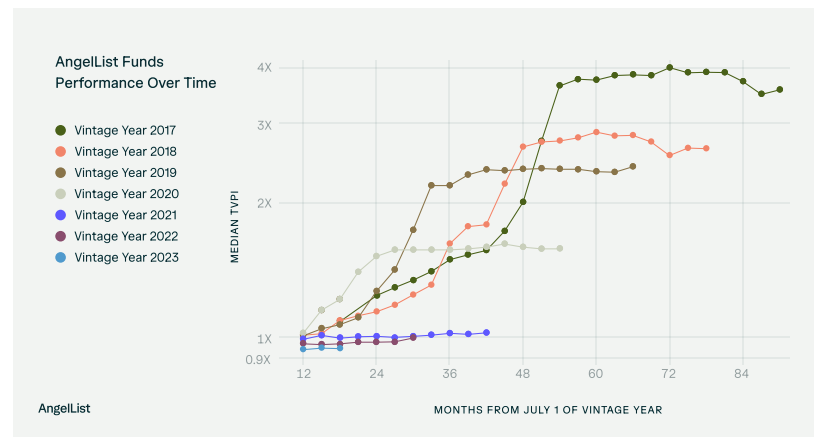

A chart from the AngelList State of Venture 2024 report is making the rounds on Twitter. Here it is:

The chart, per the source, plots the "TVPI of the typical (i.e., median) venture capital fund from different vintage years over time.”

TVPI is the value of investments (realized and paper) made by a fund, divided by the capital it has called. Or if you want to get slightly fancier, TVPI is (distributions + unrealized value - fees/carry) divided by (total contributions).

For our purposes, TVPI is a slightly generous way to vet venture performance.

The above chart uses TVPI to track different fund vintages (the year that they began investing) and their performance. Recall that most funds show modest to negative returns at the start of their life, with improving TVPI (and DPI!) over time. It’s call the J-Curve.

The vintage chart above thankfully breaks out venture fund performance by vintage year, so that we can see — apples to apples — how venture funds performed before 2021, and from 2021 through 2023, though data is more limited for the most recent cohorts.

What do we see? A collapse in venture TVPI performance. Which doesn’t bode well for later cash returns (DPI), though things could still turn around.

So what happened? Yes, valuations got out of hand. And, yes, some venture funds might have cut a corner or two on diligence. But I wonder if a key driver of lackluster venture performance in recent years is due to there being a discrete amount of money that startups can absorb at any given moment. That the market is more founder or opportunity constrained than it is capital limited. At least in the United States.

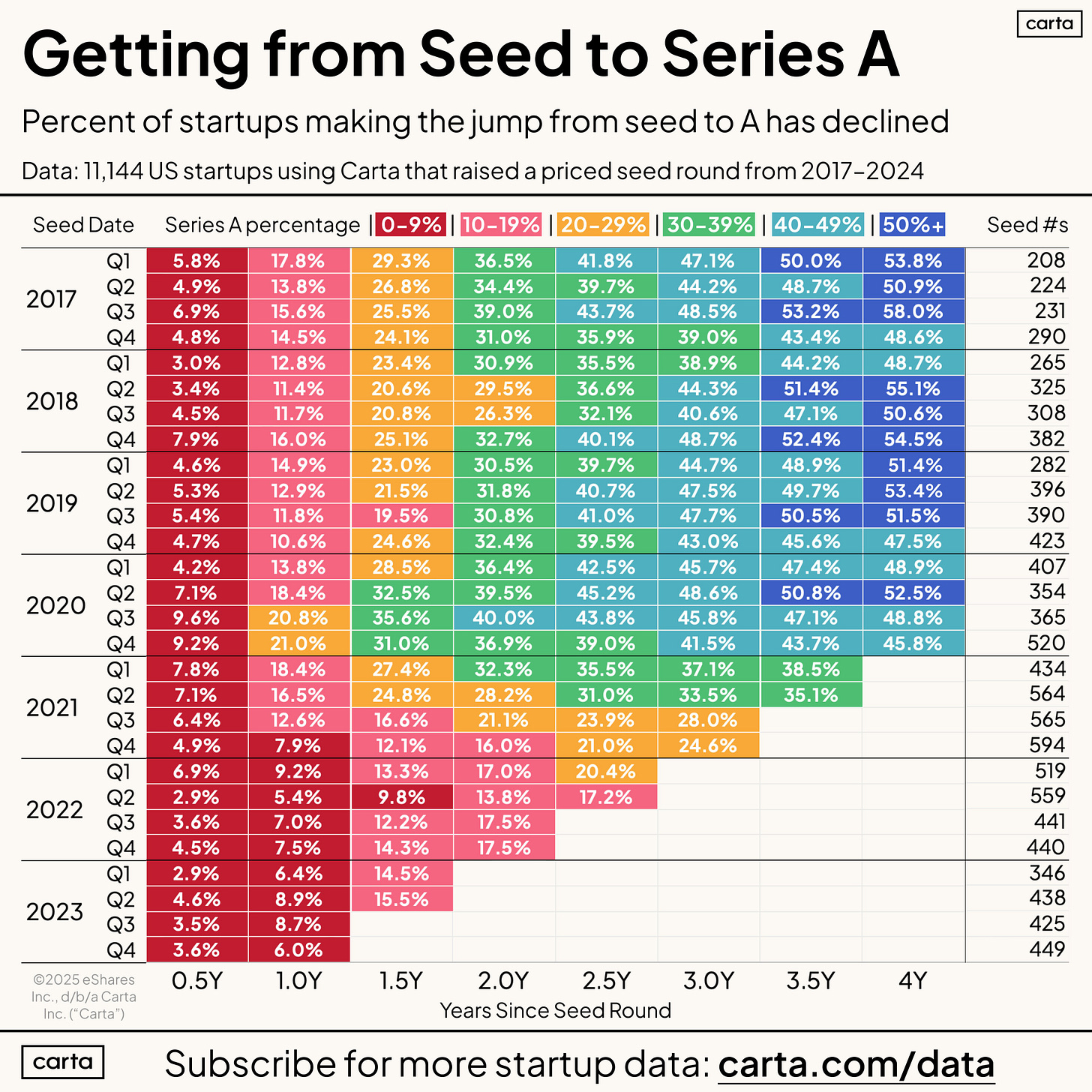

Evidence for the view can be found in a recent Carta dataset (shoutout to the Carta data team, y’all are the best):

The table shows a stable-ish graduation rate for Seed-stage startups of vintages 2017 through 2023. As you read from left to right, you can track what percentage of Seed-stage startups that raised a Seed round that year managed to close a Series A after a set timeframe.

So, a startup that raised a Seed round in Q2 2020 had a roughly 49% chance of raising a Series A by the time its Seed round was three years past. Looking at the three year post-Seed round column, it’s notable how the band of graduation — the share of startups that raised a Seed and within three years managed to raise an A — was pretty stable in the middle-40 percentage range.

Then came 2021, where we see the three-year Seed-to-A graduation rate fall into the high 30s to low 30s to high 20s to middle 20s in a single year. Put simply, the 2021-era vintage of Seed-backed startups had a much harder time raising their next, traditional venture round.

That makes sense; the venture market turned sharply in 2022, and many startups built during boom times (both in terms of their cost base, and their expectations of market pull). But more to the point, a lot more Seed deals were executed during the period. Crunchbase data provides good context here. From a January report on Seed dealmaking, Crunchbase News found that:

In 2021 there were nearly 11,000 Seed and Pre-Seed deals closed in the United States. That figure slipped to just over 10,000 deals in 2022.

In 2024, the same source found just 5,600 similar transactions.

That, during the year in which AI took over the world’s mind, and wallet.

Summing: Venture returns during the 2021-era fund vintage are poor. So, too, are Seed graduation rates from that period. While some of the churn is due to mispriced deals, CO would also hazard that a material contributing factor in lackluster venture returns for boom-era funds is predicated on backing too many total startups compared to the underlying pool of backable founders and ideas.

We’re not breaking new ground here. I could have just said “venture doesn’t scale,” or a similar hoary venture aphorism. But charts are fun, and it’s worth looking at the why behind the venerable chestnut.

Brief earnings notes

Spotify crushed Q4 earnings expectations. It’s performance is somewhat extraordinary. From the company’s earnings deck:

+35M monthly active users, “the largest Q4 in [Spotify] history,” and +10M ahead of guidance.

+11M net subscriber adds, +3M over guidance.

Revenue growth of +16% (ahead of plan), and gross margins of 32.2%, an improvement of 555 basis points year-over-year.

The company also now shits free cash flow to the tune of several billion Euro per year, and sent 10 billion Euro back to the music industry.

Shares are up around 9% in pre-market trading.

Palantir’s stock is up 23% in pre-market trading after it, too, destroyed market expectations. From its earnings download:

Revenue growth of 36% to $828 million

U.S. revenue growth of 52%, including 45% revenue growth from the United States government, bringing that portion of Palantir’s business to $343 million in the quarter.

43% YoY customer count growth, a 56% operating cash flow margin, and positive GAAP net income and even juicier adjusted profit metrics.

Of course, are we shocked that a company with connections to the people running government is doing well selling to the government? No, but Palantir is more than just a U.S. government contractor; it’s firing on all cylinders.

And then there’s PayPal, which is off around 8% in pre-market trading. Why? Despite beating revenue and EPS estimates, the company appears to be treading water:

Q4 net revenue growth of 4% was under its full-year 7% growth rate.

Total payment volume grew 7% YoY, under the company’s full-year growth rate of 10%.

GAAP profitability on an operating, operating margin, and EPS basis contracted.

You can tell that the company expected that its results wouldn’t be warmly received by the market by the fact that PayPal also announced: “[A] new $15 billion stock repurchase program,” that is “s in addition to the Company’s June 2022 stock repurchase program, which had $4.86 billion remaining authorization as of December 31, 2024.” PayPal had $15.4 billion worth of cash and equivalents and investments at the end of 2024 and $11.1 billion in debt.

Fintech is hard.

Ok that’s enough for the morning.