Netflix's insane cash generation, and venture capital's new diet

Welcome to Cautious Optimism, a newsletter on tech, business, and power.

📈 Trending Up: Chinese GDP (and yet?) … Chinese retail sales, industrial production … Nvidia revenue estimates … getting kicked upstairs … Perplexity …

📉 Trending Down: Amazon’s employee base … MacOS OpenAI exclusivity … best friends … the Lynx … WordPress …

What I missed during Netflix’s return to form

Shares of Netflix are up over 6% in pre-market trading after the Amerian streaming giant reported earnings. As my former sister publication wrote after Netflix dropped its Q3 results:

Revenue beat Bloomberg consensus estimates of $9.78 billion to hit $9.83 billion in Q3, Netflix reported after the market close on Thursday, an increase of 15% compared to the same period last year.

Netflix expects revenue to tip over the $10 billion mark in the fourth quarter, posting growth of just under the 15% it managed in Q3.

Netflix, at this age, with its competitive load, is still growing at 15% and is profitable to boot?

That from a company that saw its growth collapse to near-zero just last year?

Impressive.

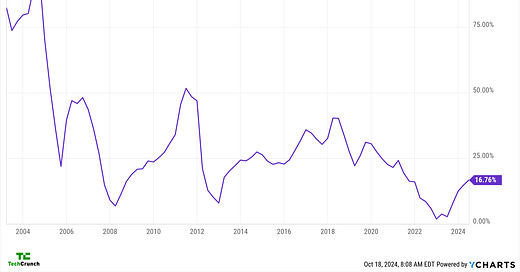

And I’m not kidding, here’s Netflix’s quarterly revenue growth (YoY) since 2023:

That Netflix has rebounded to healthy growth levels is to be applauded. And the company’s ad-support tier is growing and expected to reach “critical ad subscriber scale for advertisers in all of [its] ads countries in 2025.” Netflix did caution investors that it doesn’t “expect ads to be a primary driver of our revenue growth in 2025.” Still.

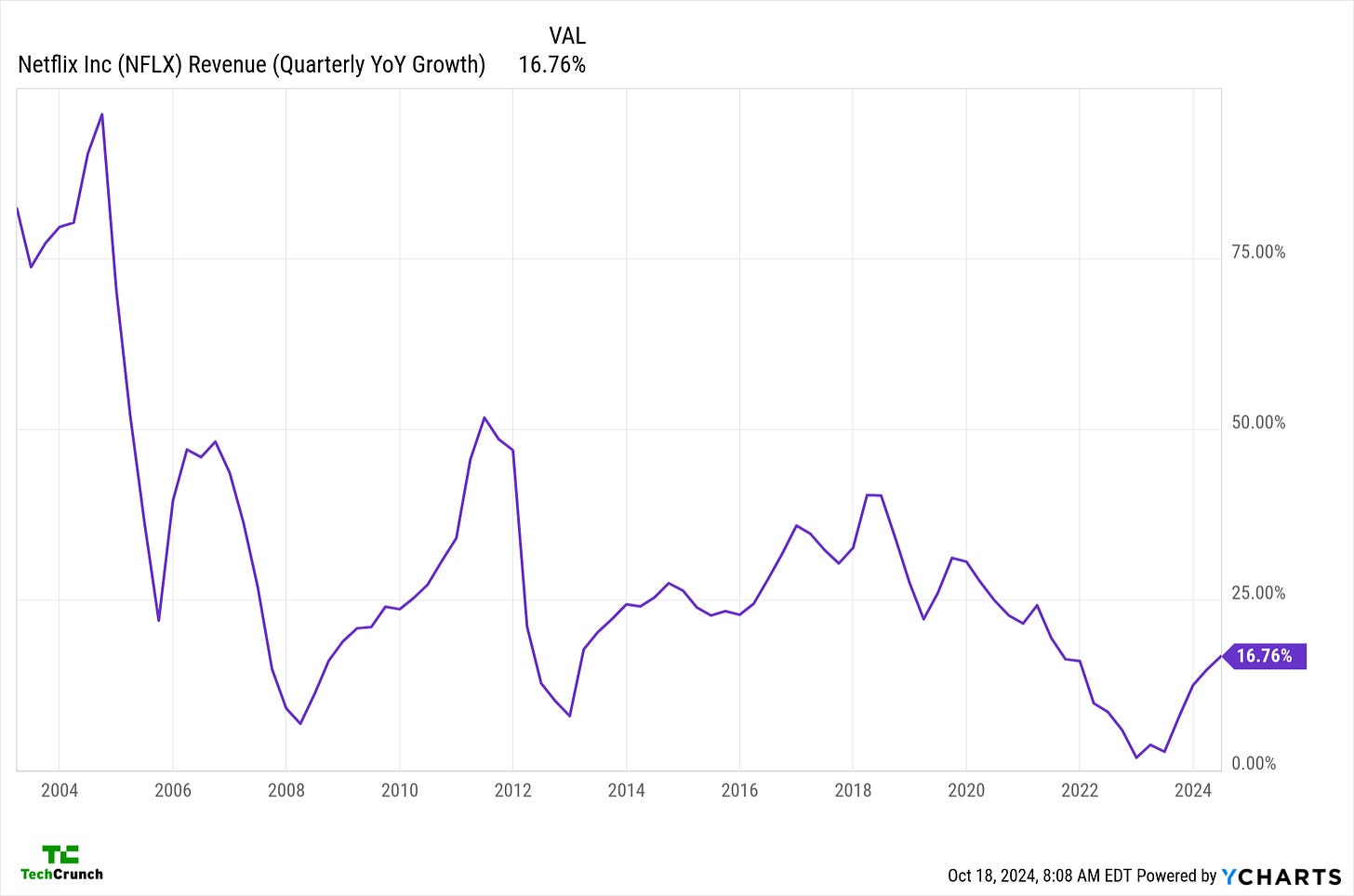

Apart from all the good news at Netflix, there’s an entirely separate story that I’ve missed: It is now a cash-generating machine:

Recall that in the 2018-2020 timeframe there was ample criticism that Netflix was spending too much, growing too little, and was in, according to a Wedbush analyst, “a vicious spiral to the bottom in content spend.”

I don’t want to dunk on critical commentary, but Netflix did prove folks wrong and is now generating mountains of cash. Hats off.

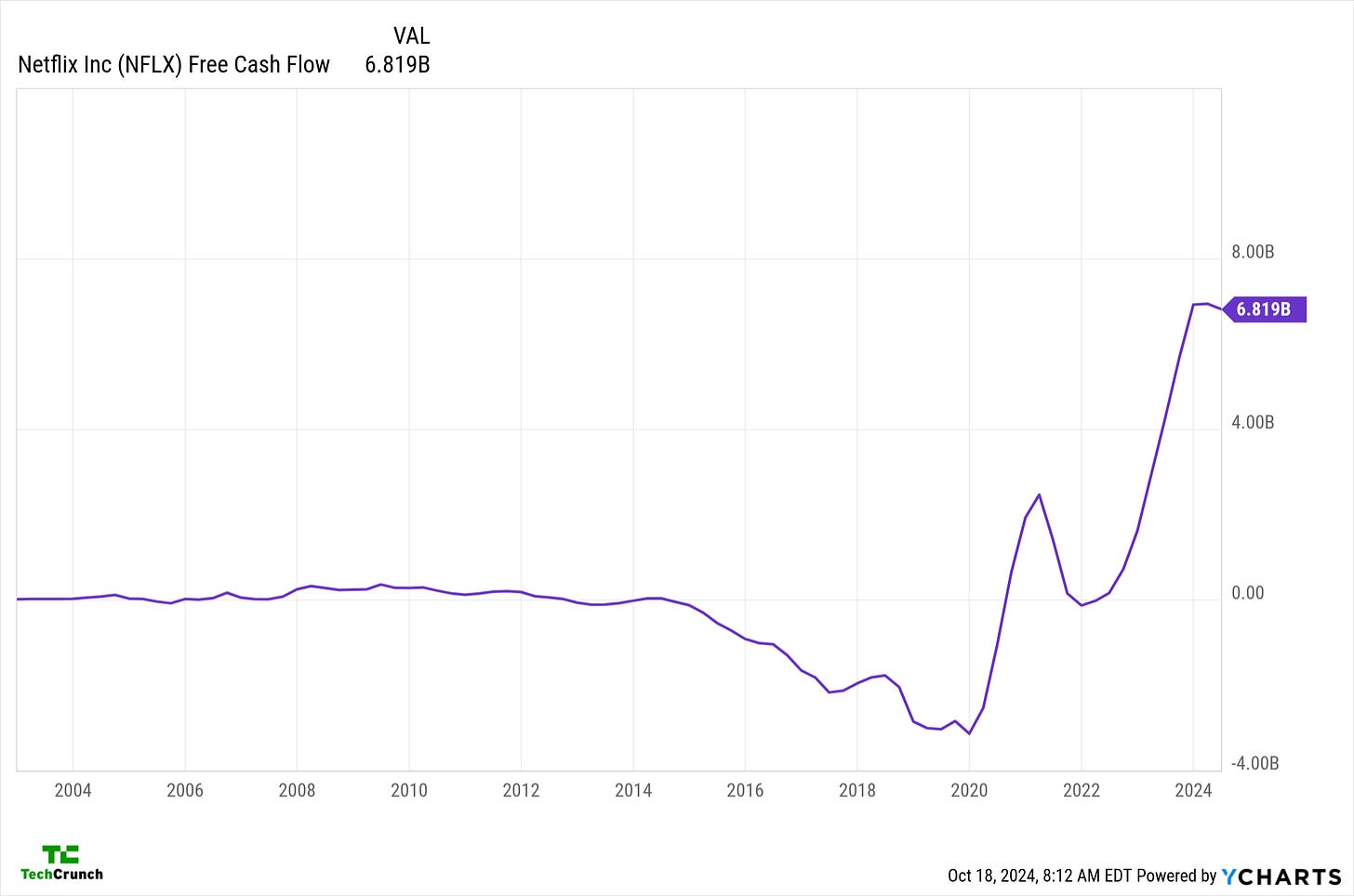

There are other companies that have shown a similar curve. Here’s Uber:

It is possible to turn a cash inferno into a cash gusher, but I wonder if we’re looking at the exceptions that prove the rule that it’s hard to do so, instead of undercutting concerns that cash burn is a risk.

Who wants to go on a diet first?

Reading a PitchBook post this morning on the slowdown in late-stage venture opportunity funds, a quote from CRV in the wake of returning just over half of its own follow-on vehicle stuck out. I had missed this, originally:

CRV: In addition, there is so much capital out there that as soon as a company shows signs of breaking out prices get driven up and return potential goes down.

There’s lots of talk in venture-land about a dearth of exits. One way to get things sold, either to acquirers or the public markets, is to price it attractively. But, as CRV notes, there’s enough cash floating around venture and venture-ish investing circles that any startup that shows “signs of breaking out” gets hit with a brick of Benjamins.

In a sense, the situation is an indictment of the pace at which breakout startups are formed; there’s more capital than there are proper receptacles. Generation-defining startups are rare by definition, but perhaps there’s fewer not-quite-generation-defining winners out there in startup-dom than some VCs and their LPs expected?

Regardless, one way to shape up the venture market today would be to reduce the total capital in play, giving startups a chance at a more ‘normal’ valuation progression as they scale, conserving some upside for later tranches and perhaps an IPO. The slimming of CRV and the decline in opportunity fund capital is a move in that direction.

But when you get paid to eat (fees off AUM), going on a diet (reducing pace of AUM accretion) is about as much fun as cutting sugar out of your diet (I’ve tried; failed).

And, speaking of exits:

PitchBook notes separately that the pace at which venture-backed companies buy one another has collapsed. From $16.5 billion worth of startup-to-startup exits in 2021, to $8.9 billion in 2022, to $4.0 billion in 2023, to just $2.8 billion through mid-October, 2024.